The best information we can ever provide investors is the mechanics of how we think about macro conditions over time rather than what we think about them at any particular time.

Consistent with this idea, we present our Macro Mechanics, a series of notes that describe our mechanical understanding of how the economy and markets work. These mechanics form the principles that guide the construction of our systematic investment strategies. We hope sharing these provides a deeper understanding of our approach and ongoing macro conditions.

Thus far in our Macro Mechanics series, we have provided our understanding of the following subjects:

Our last Macro Mechanics note described our understanding of how stocks are linked to the macroeconomy and how we think about expressing views in the stock markets to generate alpha. Today, we share our understanding of commodity markets.

Commodity markets, at their core, are simple instruments, but trading them requires some sophistication. This sophistication is required because we cannot invest in the physical commodities market in a liquid and efficient manner. Further, there is significant evidence that commodities futures offer investors a risk premium, while physical commodities do not. Thus, most liquid-market macro investors access commodities via the futures market. More recently, the proliferation of ETFs has allowed everyday investors to gain easier access to the commodities market via commodity ETFs, which do the legwork of aggregating commodity futures into indices.

Before we dive into generating alpha in commodities, let’s define commodities. Much like equities, a wide universe of commodities qualify as potential exposures—they span agricultural, industrial, energy, and precious commodities. When we invest in commodities, we refer to a broad basket of commodities, weighted in a manner that is largely consistent with each commodity’s contribution to economic activity. As macro investors, focusing on this comprehensive definition of commodities allows us to capture the linkages between macroeconomic forces and aggregate commodity prices. This approach allows us to leverage diversification and smooth away idiosyncrasies beyond macro forces, akin to index investing in equities. We zoom in on those macro forces.

Commodities are goods used as inputs in the production of other goods and services. They form the bedrock upon which more complex products are made. While the US economy has moved to have a much larger share in the form of services, none of these services would be possible without the commodities. The pervasiveness of commodities as inputs makes commodities the dominant determinant of prices further up the supply chain. When input prices rise, end-user costs will rise as businesses seek to protect their profits and pass on their increased costs. As such, commodities tend to have a nonlinear effect on prices across the economy, having an outsized impact on the aggregate price level. Said differently, commodity prices are the dominant driver of inflation in an economy over time.

This brings us to the drivers of commodity prices. Like any asset price, commodity prices are decided by the intersection of demand and supply forces. The supply of commodities is determined by the existing capacity to produce commodities and the share of that capacity utilized. Thus, while the supply of commodities can move up and down quite freely within a given capacity level in the economy, it is capped on the upside by the total existing productive capacity. Productive capacity for commodities can increase over time, but this process typically requires large capital investment over significant periods, making it a slow process. On the other side of the equation, demand for commodities is less mechanically constrained. The demand for commodities comes in two forms: the demand for the physical commodity (spot) and the demand for the financial product (futures contract). We deal with each individually. Demand for spot commodities comes from nominal spending in the economy.

Nominal spending in the economy can originate from one of three sources: income, borrowing, or the sale of assets. Income in an economy is largely a stable phenomenon, with most income generated by employment. The size of the labor force limits the growth of this employment, and while it can fluctuate throughout a business cycle, it primarily moves in tandem with the output created by workers. As such, nominal spending powered by income can be stable but has natural limitations on its impact on nominal spending. Unlike income, borrowing has no physical limitation but is constrained by the expectations of borrowers and lenders. Importantly, unlike income growth, borrowing does not have as tight a link to output and can expand far more quickly than output, creating a significant amount of excess nominal spending relative to output. Finally, the sale of assets—such as selling cash, stocks, bonds, or real estate to finance spending—can also drive nominal spending. However, large-scale asset sales are usually indicative of a shortfall in economic activity and are typically used to essentially plug a hole in spending by economic actors rather than as a durable source of ongoing spending. Economic agents are net buyers of assets over time, and sustained selling of assets is only likely in cases of financial contagion. Accounting for these features of nominal spending, leverage or borrowing drives large upswings and downswings in nominal spending and, in turn, the demand for commodities. Adding up the demand and supply factors for spot commodities, we think it's crucial to recognize that supply can move upwards and downwards but remains constrained by existing production capacity. Meanwhile, nominal spending on commodities can move more freely when financed by borrowing but much less so when financed by income or asset sales. Thus, commodity prices tend to be dominated by demand forces over time, but when we approach capacity limits, supply forces can have extremely large impacts.

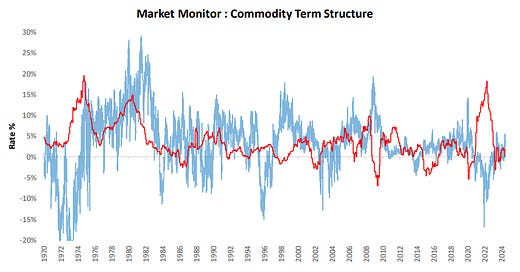

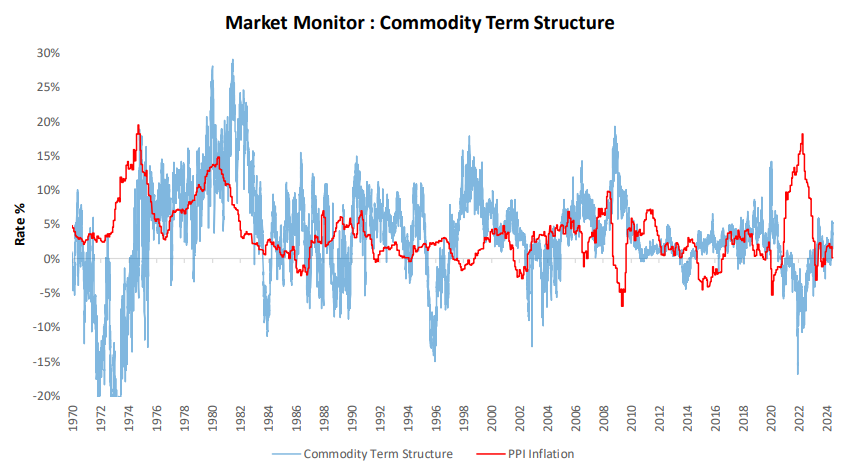

Now that we have addressed spot commodities, we can turn to futures. We think it is essential to recognize that there should be little to no risk premium for holding spot commodities in a portfolio. This is because productivity continues to make commodities easier to produce and, in turn, cheaper. This is particularly true when there is a continuously expanding production capacity and supply of commodities over time. Thus, the declining cost of spot commodities over time makes them bad investments to buy and hold indefinitely, unlike stocks and bonds. There is, however, a risk premium for owning commodity futures. This is because the demand for commodity futures primarily comes from commercial hedgers. These commercial hedgers are both consumers and producers of commodities who enter into long and short positions in commodity futures markets to hedge their bottom line and topline risk, respectively. These hedgers are comfortable with consistently losing money on their hedges, and the persistence of their positioning creates premiums and discounts to the fair value of the commodity. This is reflected in the difference between the spot commodity price and its futures price, i.e., the commodity term structure. It is crucial to recognize that the positioning of these hedgers, and in turn, the commodity term structure, is a function of ongoing conditions in fundamental macroeconomic conditions rather than market-related idiosyncrasies. Unlike stocks and bonds, the risk premiums in commodity markets are more dynamic, making them more conducive to long and short strategies. However, there is some evidence that commodity producers hedging topline risk are more persistent risk-premium underwriters, creating more of an attractive risk premium proposition on the long side. Nonetheless, commodity risk premiums require modestly higher active management to be efficiently harnessed. This requires a comprehensive understanding of the ongoing drivers of the current business cycle, estimating their continuation or reversal, and examining the drivers of the commodity term structure.

Our systematic commodity strategies are built upon the foundation of the mechanics outlined here. If you’d like to see mechanics explained in the current context, we suggest checking out the latest video update for our Prometheus Asset Allocation program:

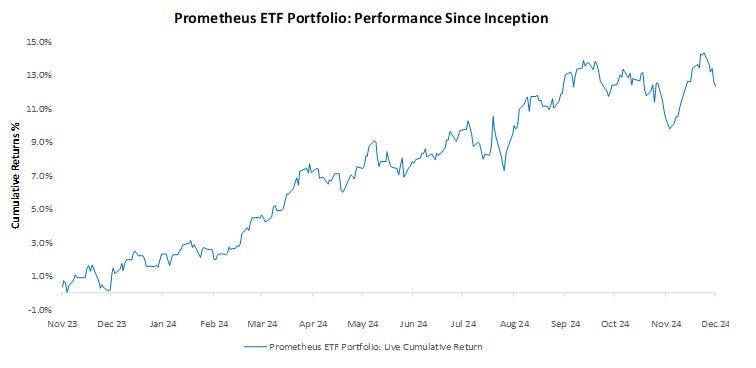

Further, if you’d like to see these principles systematically applied to trade markets, check out our Prometheus ETF Portfolio:

Until next time.