The best information we can ever provide investors is the mechanics of how we think about macro conditions over time rather than what we think about them at any particular time.

Consistent with this idea, we present our Macro Mechanics, a series of notes that describe our mechanical understanding of how the economy and markets work. These mechanics form the principles that guide the construction of our systematic investment strategies. We hope sharing these provides a deeper understanding of our approach and ongoing macro conditions.

Thus far in our Macro Mechanics series, we have provided our understanding of the following subjects:

Our last Macro Mechanics note described our comprehensive framework for determining what’s priced into macro markets. Today, we get a little more surgical, turning our gaze to the foundational asset class: treasury bonds. We offer our understanding of how bonds are linked to the macroeconomy and how we think about expressing views in the bond market.

Before expressing views on bond markets, we must have a strong understanding of their nature and biases. Bonds are fixed-income assets issued by the government that offer compensation as a reward for migrating from cash. In turn, cash seeks to entice savers by offering a return that largely neutralizes the depreciation of money caused by inflation. Thus, in order for a treasury bond to be attractive, it will seek to earn a return in excess of cash and implicitly seek to offset the impact of inflation over the course of its life. The life of a treasury varies by its tenor, ranging from a 3-month treasury bill to a 30-year treasury bond. The longer the maturity of the bond, typically the higher the interest rate we typically see on the bond in the form of its yield. This is because the further in the future we go, the more uncertainty there is about what the path of inflation will be and, in turn, what the prevailing short-term interest rate set by the Fed will be. As such, we typically see an upward-sloping term structure of interest rate for bonds, i.e., long-term bonds have higher yields than short-term bonds, to account for the increased uncertainty.

Adding all of these features up, a bond is primarily an instrument that provides excess returns over cash for the uncertainty of monetary policy in response to macroeconomic conditions. Therefore, the most important driver of the price of a bond is changes in monetary policy over the life of the bond. As mentioned, the Federal Reserve is responsible for ascribing and implementing monetary policy. Monetary policy decisions are made in accordance with the goals of maintaining modest inflation, full employment, and stable financial conditions. The Fed responds to these variables and their drivers to determine the path of short-term interest rates. Importantly, the Fed is rarely predictive in its approach but rather chooses to assess whether the current stance of monetary policy is restrictive or conducive to more economic growth. This understanding is crucial, i.e., the Fed will largely respond to the path of realized data rather than forecasted data. As such, accurately assessing the path of the Fed’s target variables offers an edge to market participants. However, it is also equally important to recognize that all sophisticated market participants are actively seeking to do the same on a daily basis, and as such, much of the Fed’s prospective path is already baked into bond yields and yield curves. Nonetheless, diligent practitioners in markets can often find insights that are not priced into consensus expectations for the path of inflation, employment, or financial stability. However, it is important to note that this is typically quite hard to sustain, as markets tend to be quite good at anticipating the likely path of the Fed over the next several months. This precise anticipation of the Fed’s path can be seen in short-term interest rate markets, ranging from a few months to almost two years.

Once we move beyond the two-year tenor, we begin to see reduced visibility on the likely path for the Fed and a change in market structure. Moving further out the curve, we see an investor preference for longer time horizons, often holding securities to maturity. At these horizons, we see the potential for the different risks being priced into bond yields beyond just the path of monetary policy. Particularly, we begin to see long-term nominal growth risks priced into bonds as term premiums. Term Premia refers to the additional return investors demand for holding a longer-term bond compared to rolling over a series of short-term bonds with the same maturity horizon. Unlike the precise calculus of what drives the Fed’s monetary policy path, the glacial movement of demand and supply forces reconciling with macro conditions drives term premia. A significant portion of the players operating in longer-duration treasuries are required to add or reduce bond exposure for reasons very different from the incremental Fed policy changes. For instance, a pension fund may increase its bond holdings because of an economic boom, resulting in large inflows. This same pension fund may need to programmatically continue to buy bonds, regardless of their pricing, for asset-liability duration matching. These dynamics can often lead to significant deviations from the fair value implied by near-term macro conditions. These demand and supply dislocations are often persistent and are reflected in term premiums. Estimating the level of term premium for a given expected policy path requires a careful evaluation of the supply of US treasuries by the Treasury and the buyers of those treasuries.

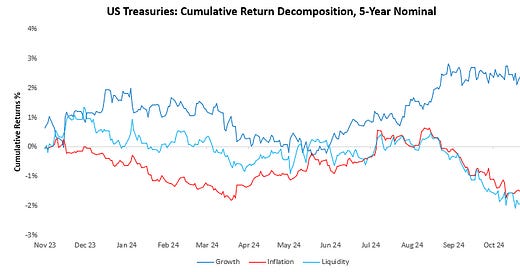

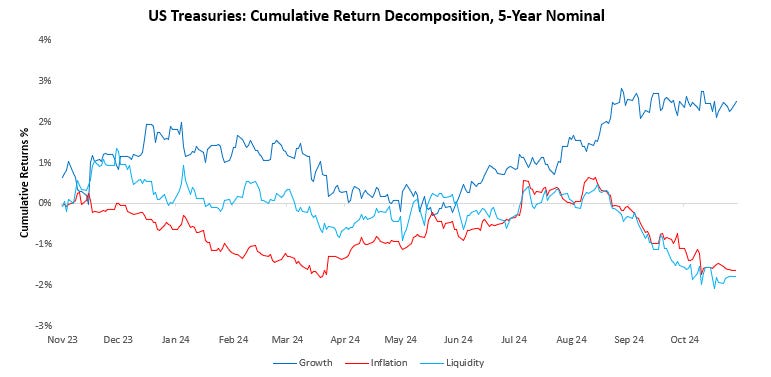

By combining these drivers, we can approximate the driver of treasury yields over time as follows:

Bond Yield = Realized Cash Rate + Expected Change In Cash Rate + Term Premium

In the above, the expected cash rate is tightly tied to the Fed’s reaction function in response to macro data. At the same time, the term premium is a function of demand and supply dynamics that are more impactful on longer-dated securities. The realized cash rate is of no consequence to those trying to generate alpha, as it is fully embedded in the price and backward-looking.

Successfully generating alpha in treasury bonds requires a careful evaluation and weighting of the impact of each on these drivers relative to one another. Often, these factors may cancel each other out, but at other times, they may align to provide a tremendous signal. 2023 was one of these times, whether bonds were mispriced in their expectations for the economy and showed excessively rich term premia. Our strategies successfully guided our clients away from bonds during this time as a function of our understanding of these drivers. We continue to apply this understanding more across our strategies.

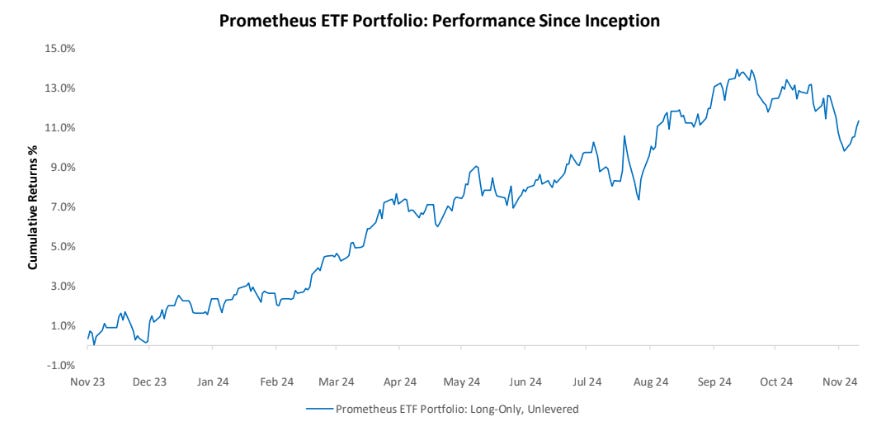

If you’d like to see these principles applied live, we recommend checking out our weekly Prometheus ETF Portfolio, which systematically applies the mechanics described here.

Until next time.