The best information we can ever provide investors is the mechanics of how we think about macro conditions over time rather than what we think about them at any particular time.

Consistent with this idea, we present our Macro Mechanics, a series of notes that describe our mechanical understanding of how the economy and markets work. These mechanics form the principles that guide the construction of our systematic investment strategies. We hope sharing these provides a deeper understanding of our approach and ongoing macro conditions.

Thus far in our Macro Mechanics series, we have provided our understanding of the following subjects:

Our last Macro Mechanics note described our understanding of how bonds are linked to the macroeconomy and how we think about expressing views in the bond market to generate alpha. Today, we turn to the asset most commonly paired with bonds: stocks.

Before discussing how we think about making bets on the stock market, we briefly provide an overview of what a stock is. A stock represents a share of ownership in a company. When you buy a stock, you are a partial company owner. Companies issue stocks to raise money for operations, expansion, or other projects. Investors are willing to invest in equities because they perceive the current price of equities to be at a discount to its future expected value due to the uncertainty around the company’s operations being successful. Over time, stocks, in aggregate, are primarily priced at a discount to future value because of the uncertainty around the uncertainty around the path of the economy. However, they may be at a premium to their future value at particular times, creating bear markets.

Three components determine the premium or discount of current equity prices to their future price. First, we have the expectations for earnings, which drive expectations for the return to shareholders. Second, we have the discount rate and its expectations over time. Third, we have the risk premium for owning equities over cash and bonds.

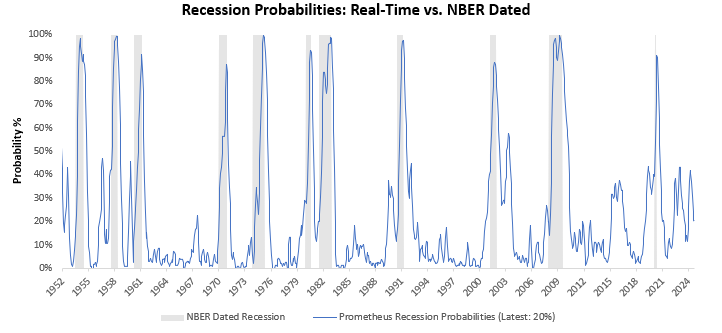

We describe each of these drivers individually to create a richer picture. We begin with earnings expectations. In the macroeconomy, earnings outcomes are largely a function of where we are in the business cycle. If the economy is experiencing a business cycle upswing, earnings expectations tend to rise, and stocks benefit from this increased expectation. During business-cycle downturns, we see the opposite, with earnings expectations falling significantly, hurting the price of equities. Crucially, the foundation of earnings expectations is largely built upon what companies themselves provide in terms of their guidance. Fully aware of market-pricing dynamics, companies often provide earnings expectations in a manner where they modestly underpromise in order to overdeliver and continue to have support for their equity prices. This creates a dynamic where stock markets tend to constantly have an upward drift toward their earnings expectations over time, benefiting stock prices. While these individual companies are experts in their own sales and profit outcomes, they are largely blind to macroeconomic developments. Thus, while corporate guidance may contain some modest references to the macro circumstance, it will never be a series of macroeconomic forecasts. Adding this dynamic up across all individual companies, aggregate corporate profit guidance is driven by macro forces but often devoid of very precise and timely macroeconomic relationships. As such, significant business cycle accelerations and decelerations are largely not captured by corporate guidance for earnings. Therefore, a timely understanding of business cycle conditions and their pass-through to corporate profits in a manner that is not accounted for in corporate earnings guidance can offer a modest edge in timing equity markets.

Next, we turn to policy rates and their expectations. A stock is a claim on a series of future expected cash flows. A discount rate is used to discount these cashflows ’ present value, represented in the stock price. This discount rate reflects the current risk-free rate, expectations for the evolution of this policy rate, and the risk premium for owning equities over risk-free assets. We focus on the first two components of this discount rate before moving on to the second in the next section. Recall that risk-free assets, i.e., those without credit risk, are US treasuries across the yield curve. These risk-free yields are the baseline atop which all discount rates, including those of equities, are built. Said differently, the yield on every asset is equal to the discount rate plus a premium or discount, depending on macro conditions. In the case of stocks, treasury yields play a large role in determining the variations in discount rates over time. Recall that treasury yields are a function of changes in policy rate expectations, driven by changes in employment, inflation, and financial stability relative to the Federal Reserve’s objectives. Thus, as treasury yields rise to price in tighter conditions relative to the Fed’s objectives, equity markets face the headwind of rising discount rates. Meanwhile, equity markets rise when treasury yields fall to price in looser conditions relative to the Fed’s objectives. Therefore, a timely assessment of the variation of employment, inflation, and financial stability from the Fed’s objectives and its prospective reaction function can offer insight into the future path of stock returns.

Finally, we turn to the equity risk premium. As noted above, the stock discount rate reflects the current risk-free rate, expectations for the evolution of this policy rate, and the risk premium for owning equities over risk-free assets. This premium reflects the incremental risk of owning equities over risk-free treasury securities. This risk premium largely reflects that corporations may be unable to achieve what’s price dint their expectations or return monetary value to their shareholders. Movements in this risk premium are driven by demand and supply conditions, which drive investor allocation. As we progress through an economic cycle, investor exposure to equities usually peaks, driving a significant compression in the equity risk premium. The equity risk premium once again expands as investors reduce their stock exposures. There is no precise number at which equity risk premiums should settle, but equity risk premiums over time should not be too cheap or expensive to bond risk premiums and commodities. The equity risk premium typically does not catalyze moves in equities by itself but rather potentiates the size of prospective moves. Thus, a careful evaluation of equity risk premiums relative to bond and commodity risk premiums allows us a better understanding of the potential for upside or downside moves.

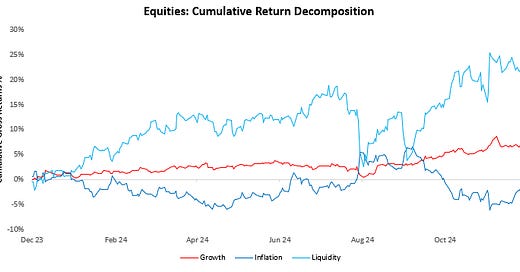

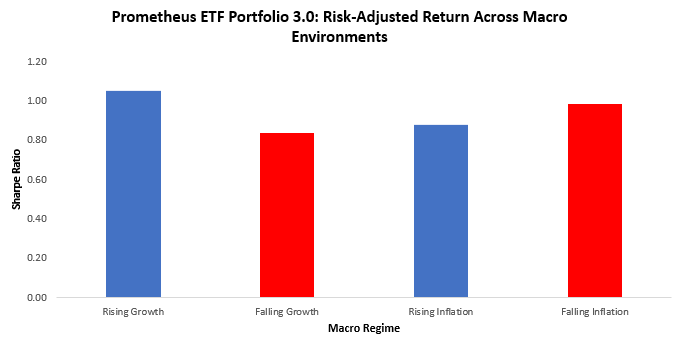

We can now add up all the features described above to provide a holistic framework for understanding what drives stock markets and how to think about generating alpha for them:

Stock prices reflect a series of future expected earnings whose present value is calculated using a discount rate that embodies the current risk-free rate, the expected change in the risk-free rate, and an equity risk premium. Generating alpha requires carefully evaluating each of these drivers and a quantified understanding of their relative impacts on equity prices. While focusing on one driver may work at any particular point, we believe a durable approach to alpha will seek to account for all of these drivers over time.

If you’d like to see these principles applied live, we recommend checking out our weekly Prometheus ETF Portfolio, which systematically applies the mechanics described here.

You can also watch a recent Asset Allocation update from October. In the video, Aahan, our Founder & CEO, walks through all of these conditions and how they drive our systematic portfolio positioning.

Until next time.