The best information we can ever provide investors is the mechanics of how we think about macro conditions over time rather than what we think about them at any particular time.

Consistent with this idea, we present our Macro Mechanics, a series of notes that describe our mechanical understanding of how the economy and markets work. These mechanics form the principles that guide the construction of our systematic investment strategies. We hope sharing these provides a deeper understanding of our approach and ongoing macro conditions.

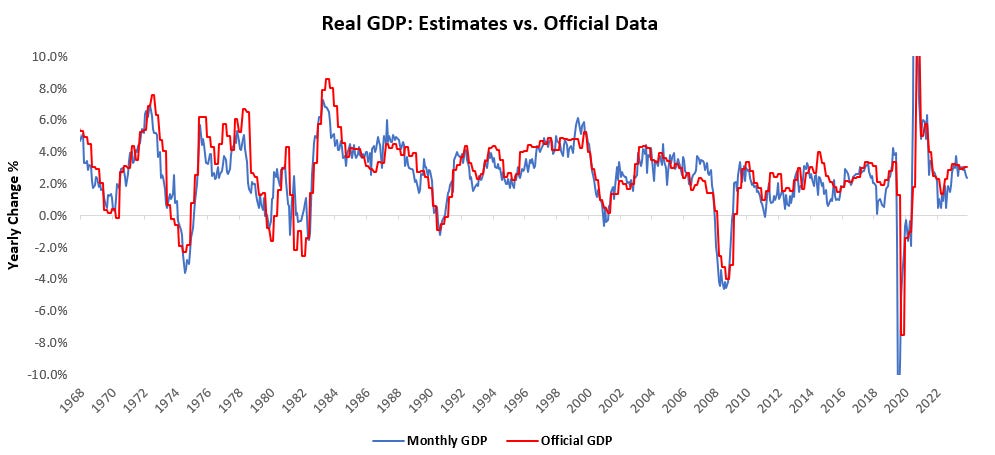

Our last two macro mechanics notes described our understanding of growth and inflation. We highly recommend reading through them before today’s note. Starting with Growth:

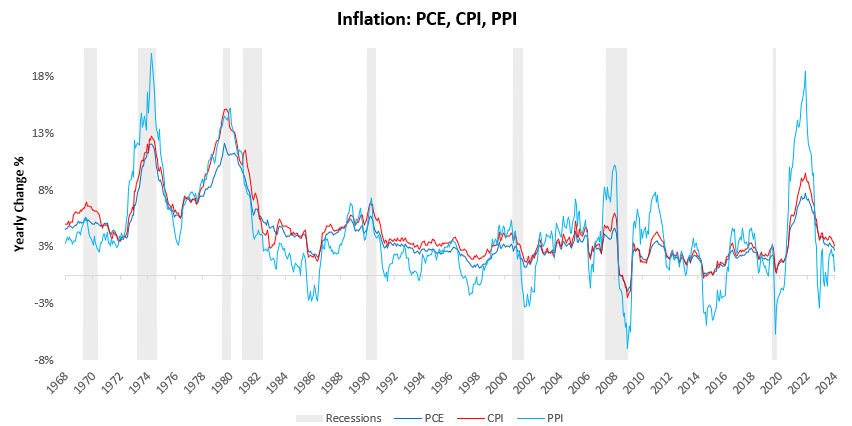

And then inflation:

Today, we offer our understanding of liquidity.

Unlike growth and inflation, liquidity has no standard definition. In the post-2008 financial crisis, liquidity has become an increasingly important component of understanding financial markets. However, it is a mechanism that predates this era. In this note, we will offer our internal definition of liquidity and how it impacts markets.

We have often stated that liquidity is the flow of cash and cash-like assets that potentiates spending in the real and financial economy. Liquidity is a balance sheet concept that measures the potential energy stored in balance sheets, which can be released into financial markets and the economy. Ample liquidity is conducive to balance sheet resiliency and potentiates balance sheet expansion.

A crucial and foundational pillar to understanding liquidity is that every asset exists somewhere on the liquidity spectrum. A bank reserve is more liquid than a treasury bond, a treasury bond is more liquid than a bank loan, and a bank loan is more liquid than real estate. As such, every asset exists somewhere on the liquidity spectrum, but they differ in where they sit in the liquidity hierarchy and, thus, in their relative contribution to liquidity conditions.

The relative contribution of a balance sheet item to aggregate liquidity conditions is a function of its relative size and its relative risk. The relative size component is straightforward: the more nominal dollars outstanding of an asset as a percentage of the private sector balance sheet, the more impact it has on overall liquidity conditions. The relative risk component is more nuanced, with two components defining an asset's riskiness: the duration and the credit risk. We begin with duration. As the prospective life of an asset increases, the riskiness of the future cash flows risks as uncertainty increases. This exposes the asset to potential changes in interest rates, growth, and inflation, increasing its price volatility and potential for loss. As such, the more duration we introduce into private sector balance sheets, the more risk we impose. As such, long-term securities like stocks, long-term bonds, and long-term borrowing have a deleterious effect on liquidity conditions relative to short-term assets like bank reserves, Treasury bills, and commercial paper. The credit risk of aggregate balance sheet items also impacts liquidity conditions similarly. The credit risk of each asset is a function of the stability and reliability of cash flows produced by the issuing entity. As such, government assets such as Treasuries and MBS have virtually no credit risk relative to private sector assets. A crucial part of this understanding is that these risks vary over time, i.e., securities' duration and credit profile are constantly changing with market prices. As such, the liquidity profile of these assets is also dynamic.

Given these characteristics, it is crucial to recognize the extremely outsized role that the government plays in pulling these levers. The Fed directly controls interest rates, which has a dramatic impact on the value of all assets. The government can also run large deficits without impacting its creditworthiness, as it is the originator of all currency and is not mechanically ever limited in its ability to meet its obligations. Finally, the use of quantitative monetary policy by the Federal Reserve allows the government to inject and remove riskless bank reserves from the financial system, thereby having significant implications for liquidity. Thus, while the private sector is an important part of the liquidity ecosystem, it is essential to recognize that the ongoing objectives of the government will largely dominate liquidity conditions.

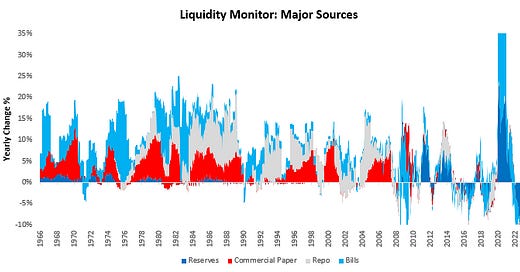

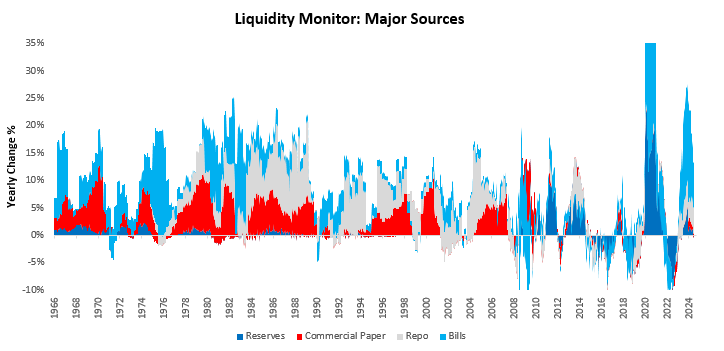

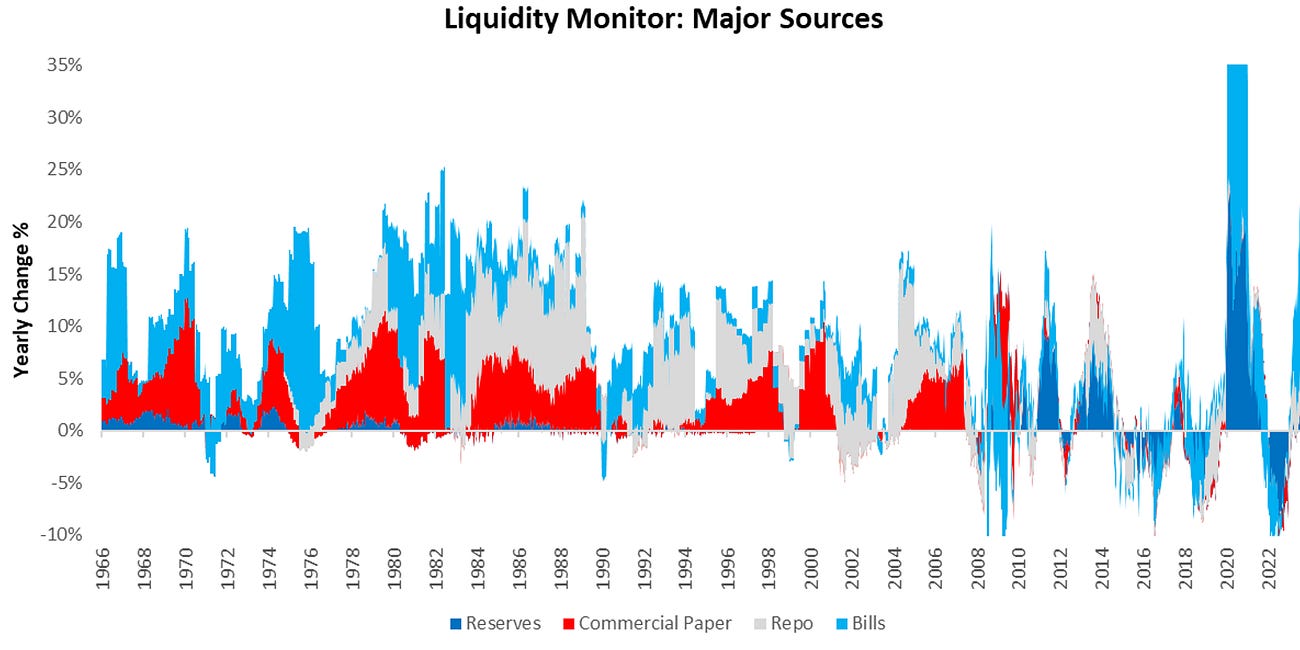

This understanding is consistent with today’s macro circumstances. The government, through a combination of high Treasury bill issuance, elevated reserve balances in the banking system, and implicit guarantees in the mortgage market, has created an environment where government assets loom large on private sector balance sheets. In the post-financial crisis world, the role of the private sector in creating short-term liquid assets has declined dramatically, with the commercial paper market shrinking substantially. While the role of the corporate bond market remains a significant part of markets, it is dwarfed by the scale of government action across issuance relative risk. A crucial mechanical outcome of these recompositions is that liquidity has largely taken on a countercyclical role in the economy relative to history, given this outsized government role. When the economy begins to suffer, liquidity is now more likely to rise than in previous cycles.

Now that we have defined the levers that drive liquidity conditions, we discuss their implications. The larger the preponderance of low-duration, low-risk securities on private sector balance sheets, the more potential to take on risk. Liquidity supports risk-taking by encouraging spending in the economy via dissaving and creating a stable base atop which new borrowing can be created. The lack of liquidity encourages the opposite. Importantly, liquidity in itself cannot create risk-taking. Where liquidity will flow is contingent upon growth and inflation outcomes. During deflationary periods, liquidity will seek government securities; during inflationary ones, private sector securities, etc. Liquidity can create the potential for risk-taking, but how that risk is distributed will depend on growth and inflation. This understanding is crucial to be able to use liquidity as a viable barometer for investing in macro markets. Liquidity in itself cannot create a strong outcome for any particular asset (stocks, bonds, commodities). The relative returns between assets will be determined primarily by growth and inflation.

Synthesizing these mechanics: Liquidity is the flow of cash and cash-like assets that potentiates spending in the real and financial economies. Every asset contributes to this flow, and an asset's contribution to liquidity is determined by its relative size and risk characteristics. Government policy actions have come to dominate liquidity conditions, making liquidity an increasingly countercyclical force for the economy and markets. Liquidity conditions potentiate returns across assets, but the economic environment determines the distribution of returns between assets.

We hope this helps illuminate our mechanical understanding of liquidity. Consistent with these principles, we have built our systematic investment process around a rigorous understanding of conditions.

If you want to see how we apply these mechanics to macro and market conditions, you can look at our most recent note on liquidity.

Until next time.

Top drawer content as always

Nice post! It would be interesting to dig deeper into the four major sources of liquidity and how they independently impact total liquidity: reserves, Treasury bills, commercial paper, and repos. Thanks!